Sounds - 16th April 1988

Sounds - 16th April 1988

(transcription from the old Shadow Cabinet website)

The Starfish Enterprise

Sounds - April 16th 1988

Steve Kilbey, bassist, singer and principle songwriter of The Church, sits down at the breakfast table in his New York hotel and takes a small envelope out of his pocket. He empties it, and half a dozen assorted vitamin and mineral tablets fall onto the table. He gives me a rundown on their contents and rattles them down his throat.

Kilbey, with his soft voice and soft good looks, seems something of a misfit in New York. Later he tells me that he doesn’t feel drawn to such "a great big seething mass. I don’t particularly like walking down 7th Avenue, being pushed along by this bloody great teeming wave of, um, people. But I’m sort of here to do a job…"

Then he heads off in the general direction of 7th Avenue for a round of US radio interviews. The new Church LP ‘Starfish’ has just entered the Billboard chart at 93. Kilbey may tell me he’s come close to a nervous breakdown after only five days on the road but he’s the polar opposite of the usual rock ‘n’ roll picture of health. That probably has something to do with the eight years he’s spent on and off the road with The Church.

After those eight years The Church , who’ve long been stars in their native Australia, remain an arcane proposition to most of the UK record-buying public. Anyone who casually remembers the name recalls affectionately their near-hit of 1982, ‘The Unguarded Moment’.

This year, they’ve had another near-hit with ‘Under The Milky Way’ which collected substantial daytime radio play but still didn’t quite manage to get there - the story of The Church in the UK.

But they retain a fervent cult audience: a few weeks ago they sold out two night at London’s Marquee and when I arrived, someone else had nabbed the tickets that were waiting for me at the door. This week they’re back to play a sold-out show at London’s Town and Country club. They’ve made six albums, for various labels: their last, ‘Heyday’ appeared on Warners in 1986, and ‘Starfish’ is on Arista. Someone has always put another push behind The Church, and three of the group’s four members have also managed to sneak out solo albums. It’s been an odd career.

"It isn’t really as bad as people think," murmurs Kilbey, the morning after their two shows at New York’s Bottom Line club. "You know, people have paid for us to make six albums. We’ve eked a living, survived, stayed together, had a lot of good times, seen a lot of different countries. People always see this negative thing. Oh, they’ve been bashing their heads against the wall for eight years..."

You don’t feel like that?

"Well, on a real macro level, I guess, yes. We haven’t been hugely successful. But I don’t think the ultimate aim should be a number one all around the world at once. Just maintaining your existence is an achievement in itself..."

There was a feeling that ‘UTMW’ would finally get you a hit single in Britain.

"Yeah. And it died. It’s funny. But who can say why? It’s just luck. To be really crass about it, the album’s doing really well in America, and Australia, and Germany. We don’t really need it. England would be the icing on the cake. On the other hand, every time we play in England we get the best response in the world. At the Marquee the other night, they just fucking roared! All the way through."

It’s when The Church take the stage that the paradoxes smack you in the face. ‘Starfish’, their second consecutive great album, finds the poetic essence of Kilbey’s lyricism mirrored in the music. Songs like ‘Destination’, ‘UTMW’ and ‘Lost’ pursue a hazily outlined spiritual destiny. And their sound, with its wash of guitars and deceptively complex melodic structure, is too subtle and evocative ever to dive headlong into the stadium rock pool where some of their statuesque rock rhythms dip strategic toes.

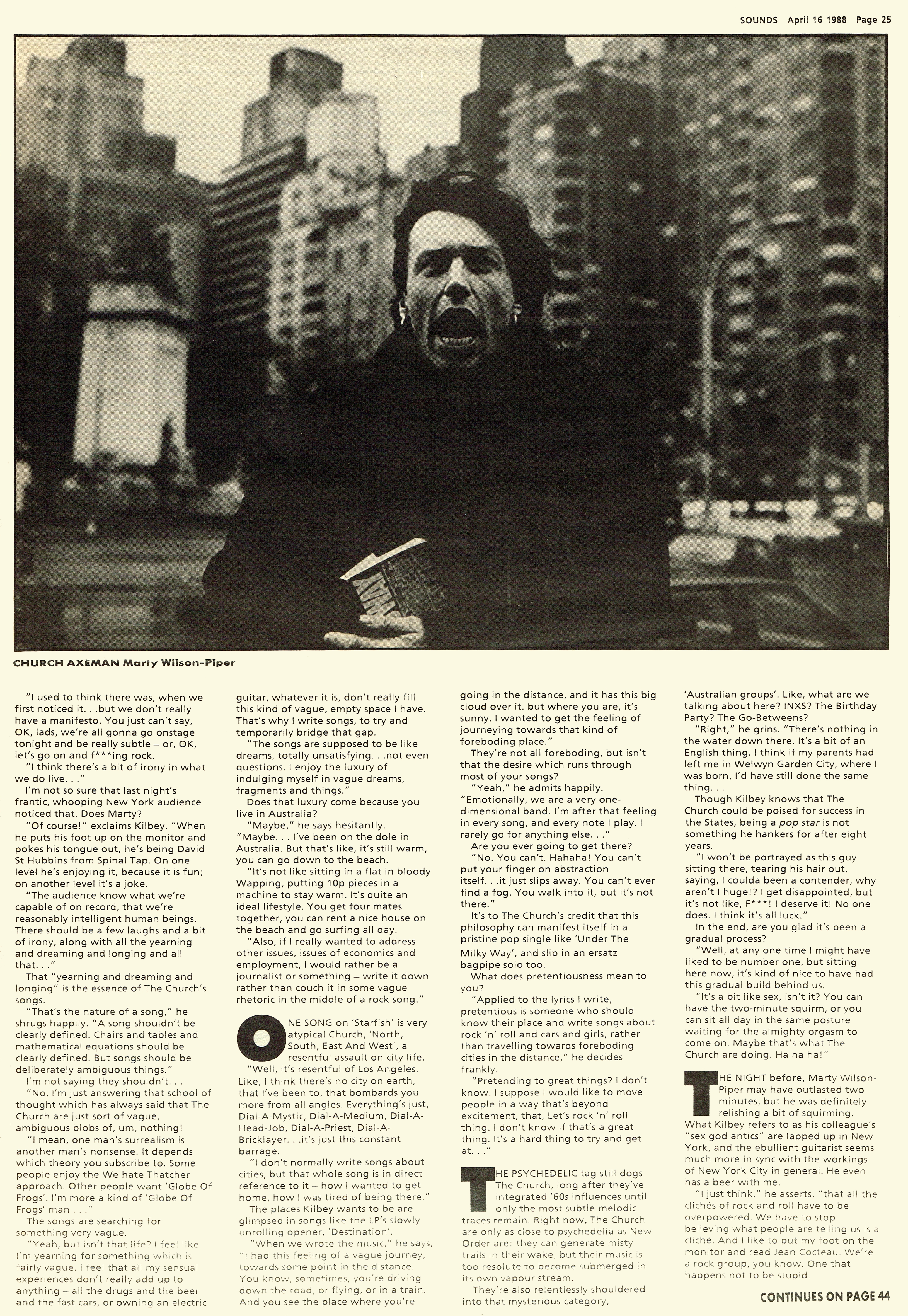

But at the Bottom Line, the delicacy evaporates, bar the Verlaine-ish inflections of guitarist Peter Koppes. Drummer Richard Ploog’s beat gets louder and more strident and guitarist MWP steps with relish into an arm-waving, often hilarious, sometimes self-conscious axeman posture. At least one layer of mystery is stripped off. And one fascinating contrast - between the extrovert stage manner and introverted songs - is instigated.

“Yeah,” says Kilbey carefully. “Well, what happens is just pretty random. You can’t really be delicate all the time onstage. Being delicate is all very well on record. When we first started we were delicate live. But I guess we’re a confused and confusing band. We have elements of subtlety, and we have elements of Spinal Tap...”

Is there a conflict between the two sensibilities?

“I used to think there was, when we first noticed it...but we don’t really have a manifesto. You just can’t say, OK, lads we’re all gonna go onstage tonight and be rally subtle - or, OK, let’s go on and fucking rock. I think there’s a bit of irony in what we do live...”

I’m not so sure that last night’s frantic, whooping New York audience noticed that. Does Marty?

“Of course!” exclaims Kilbey. “When he puts his foot on the monitor and pokes his tongue out he’s being David St Hubbins from Spinal Tap. On one level he’s enjoying it, because it’s fun; on another level it’s a joke. The audience know what we’re capable of on record, that we’re reasonably intelligent human beings. There should be a few laughs and a bit of irony, along with all the yearning and dreaming and longing and all that...”

That “yearning and dreaming and longing” is the essence of The Church’s songs.

“That’s the nature of a song,” he shrugs happily. “A song shouldn’t be clearly defined. Chairs and tables and mathematical equations should be clearly defined. But songs should be deliberately ambiguous things.”

I’m not saying that they shouldn’t...

“No, I’m just answering that school of thought which has always said that The Church are just some vague, ambiguous blob or, um, nothing! I mean, one man’s surrealism is another man’s nonsense. It depends on which theory you subscribe to. Some people enjoy the ‘We Hate Thatcher’ approach. Other people want ‘Globe Of Frogs’. I’m more a kind of ‘Globe of Frogs’ man...”

The songs are searching for something very vague.

“Yeah, but isn’t that life? I feel like I’m yearning for something which is fairly vague. I feel that all my sensual experiences don’t really add up to anything - all the drugs and the beer and the fast cars, or owning an electric guitar, whatever it is, don’t really fill this kind of vague, empty space I have. That’s why I write songs, to try and temporarily bridge that gap. The songs are supposed to be like dreams, totally unsatisfying...not even questions. I enjoy the luxury of indulging myself in vague dreams, fragments and things.”

Does that luxury come because you live in Australia?

“Maybe,” he says hesitantly. “Maybe...I’ve been on the dole in Australia. But that’s like, it’s still warm, you can go down the beach. It’s not like sitting in a flat in bloody Wapping, putting 10p pieces in a machine to stay warm. It’s quite an ideal lifestyle. You get four mates together, you can rent a nice house on the beach and go surfing all day. Also, if I really wanted to address other issues, issues of economics and employment, I would rather be a journalist or something - write it down rather than couch it in some vague rhetoric in the middle of a ‘rock song’.”

One song on ‘Starfish’ is very atypical Church, ‘NSEW’, a resentful assault on city life.

“Well, it’s resentful of LA. Like, I think there’s no city on earth, that I’ve been to, that bombards you more from all angles. Everything’s just Dial-a-Mystic, Dial-a-Medium, Dial-a-Head-job, Dial-a-Priest, Dial-a-Bricklayer...it’s just this constant barrage. I don’t normally write songs about cities, but that whole song is in direct reference to it - how I wanted to get home, how I was tired of being there,”

The places Kilbey wants to be are glimpsed in songs like the LP’s slowly unrolling opener, ‘Destination’.

“When we wrote the music”, he says, “I had this feeling of a vague journey, towards some point in the distance. You know, sometimes, you’re driving down the road, or flying, or in a train. And you see the place where you’re going in the distance, and it has this big cloud over it, but where you are, it’s sunny. I wanted to get the feeling of journeying towards that kind of foreboding place.”

They’re not all foreboding, but isn’t that the desire which runs through most of your songs?

“Yeah,” he admits happily. “Emotionally, we are a very one-dimensional band. I’m after that feeling in every song, and every note I play. I rarely go for anything else...”

Are you ever going to get there?

“No. You can’t. Hahaha! You can’t put your finger on abstraction itself...it just slips away. You can’t ever find a fog. You walk into it, but it’s not there.”

It’s to The Church’s credit that this philosophy can manifest itself in a pristine pop single like ‘UTMW’, and slip in an ersatz bagpipe solo too. What does pretentiousness mean to you?

“Applied to the lyrics I write, pretentious is someone who should know their place and write songs about rock’n’roll and crass and girls, rather than traveling towards foreboding cities In the distance,” he decides frankly. “Pretending to great things? I don’t know. I suppose I would like to move people in a way that’s beyond excitement, that, Let’s Rock’n’Roll thing. I don’t know if that’s a great thing. It’s a hard thing to try and get at...”

The Psychedelic tag still dogs The Church, long after they’ve integrated ‘60s influences until only the most subtle traces remain. Right now, The Church are only as close to psychedelia as New Order are: they can generate misty trails in their wake, but their music is too resolute to become submerged in its own vapour stream. They’re also relentlessly shouldered into that mysterious category, ‘Australian group’. Like, what are we talking about here? INXS? The Birthday Party? The Go-Betweens?

“Right,” he grins. “There’s nothing in the water down there. It’s a bit of an English thing. I think if my parents had left me in Welwyn Garden City, where I was born, I’d have still done the same thing...”

Though Kilbey knows that The Church could be poised for success in the States, being a pop star is not something he hankers for after eight years.

“I won’t be portrayed as this guy sitting there, tearing his hair out, saying I coulda been a contender, why aren’t I huge? I get disappointed, but it’s not like, Fuck! I deserve it! No one does. I think it’s all luck.”

In the end, are you glad it’s been a gradual process?

“Well, at any one time I might have liked to be No.1, but sitting here right now, it’s kind of nice to have had this gradual build behind us. It’s a bit like sex, isn’t it? You can have the two-minute squirm, or you can sit all day in the same posture waiting for the almighty orgasm to come on. Maybe that’s what The Church are doing. Ha Ha Ha!”

The night before, Marty Willson-Piper may have outlasted the two minutes, but he was definitely relishing a bit of squirming. What Kilbey refers to as his colleague’s ‘sex god antics’ are lapped up in New York, and the ebullient guitarist seems much more in sync with the workings of NYC in general. He even has a beer with me.

“I just think,” he asserts, “that all the clichés of rock and roll have to be overpowered. We have to stop believing what people are telling us is a cliché. And I like to put my foot on the monitor and read Jean Cocteau. We’re a rock group, you know. One that happens not to be stupid. Take David Bowie. When he was doing ‘Hunky Dory’ and ‘Life On Mars’, he was jumping around onstage in a catsuit! At the moment, I don’t know if anyone else is doing it, dealing with thought-provoking images and executing it in an extrovert kind of way. It’s always either Pink Floyd and David Gilmour’s getting fat and standing still, or it’s The Cult writing these funny lyrics and jumping around. You know?”

Here he has hit on the unique facet of The Church’s live show, the one which should help propel them beyond the college radio circuit and into the big league, without any need to resort to the rabble-rousing tactics of their rock contemporaries. If they’d play more often in Britain, it might work there too. Not that Marty - the only member of The Church who doesn’t reside in Australia, having opted for Sweden a few years ago - is any more worried than Kilbey. Much less in fact. He thinks Britain ‘deserves to drown in its own cynicism’.

Thanks, Marty. Count me out. In fact he does - and presumably all The Church’s UK fans. He also manages to express the group’s resilient character - and perhaps also the reason why Steve Kilbey’s gentle chuckle over his sex metaphor can easily turn out to be an understated last laugh.

“I’ve always thought The Church is the sort of band people could, um, get into, and follow,” he confides completely unfashionably, “like in the ‘70s. We’ve always made a point of making albums. We don’t make dance music. We don’t do anything that’s remotely black. We don’t do anything that’s commercially oriented, really. We don’t do singles that are fashionably inspired. We’re just a band who, when they get together, think they create something which couldn’t be created by just anybody. Now, if that isn’t a relevant reason to exist, then what is?”

What indeed...

Return to 1988 index