Option - November/December 1988

Option - November/December 1988

(transcription from the old Shadow Cabinet website)

From Options magazine, circa 1988

Keeping the Faith:

The solo pursuits of the members of the Church

by Brad Bradberry

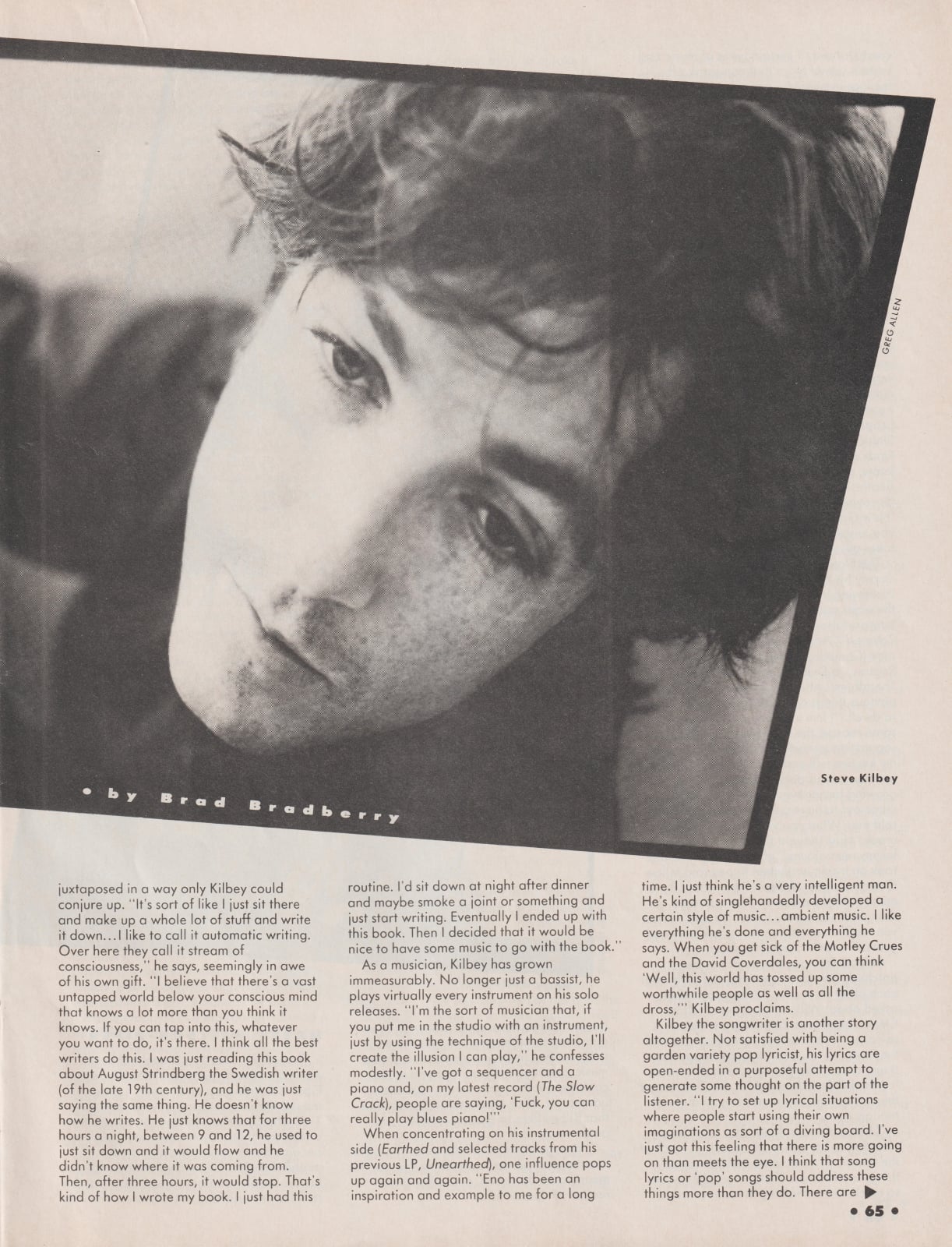

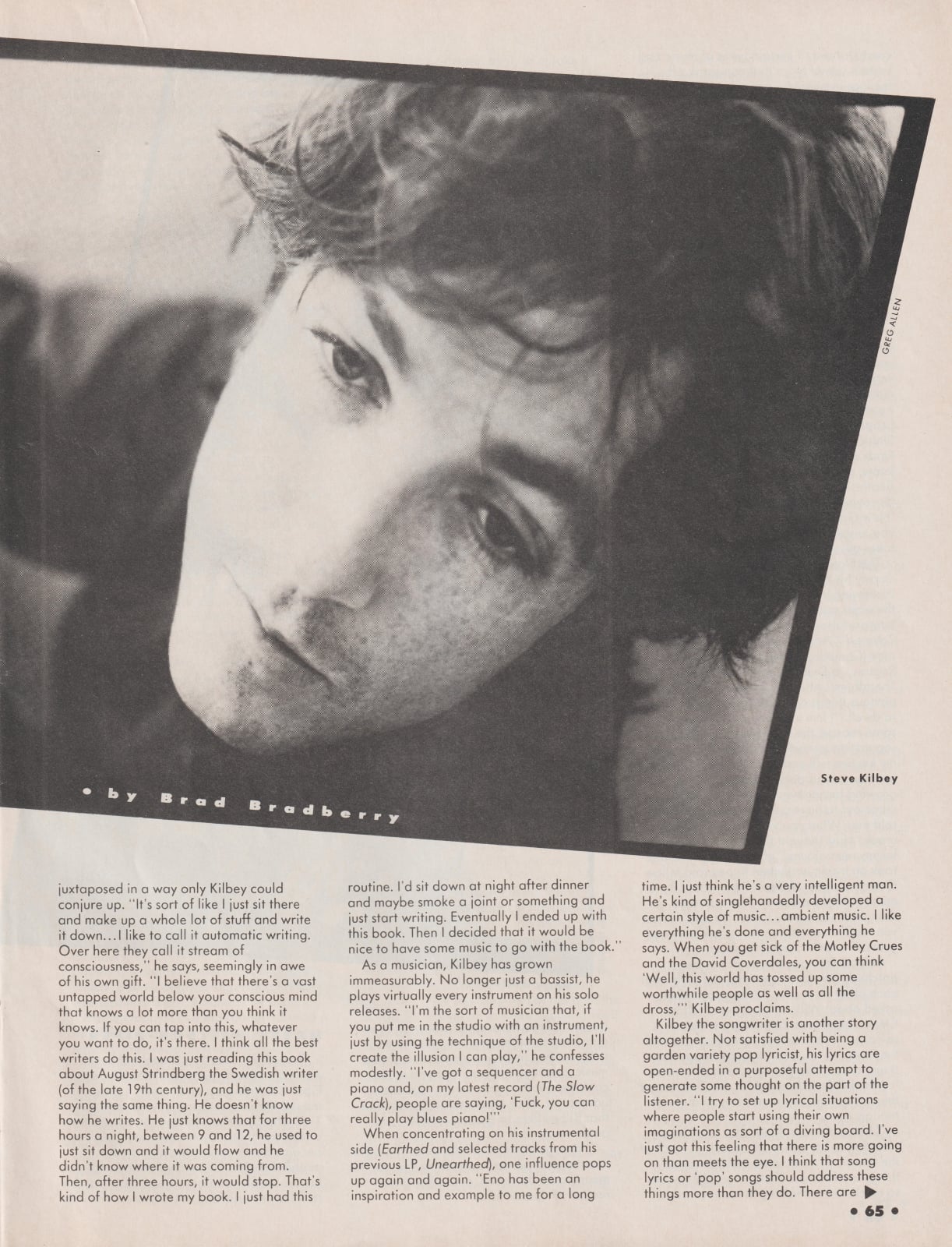

S T E V E K I L B E Y

"I think there is more going on in the world than making money and going home

to your wife," says Steve Kilbey, the bassist, singer, songwriter, and

creative nucleus of Australian pop group the Church. Kilbey, a prolific

songwriter feeling the creative constraints of his band, has been releasing

solo projects since 1985. "When you're on your own, if you get an idea, you

can do it the next day," he asserts. "Whereas the situation with the Church is

that it's just such a huge bloody decision if you want to go down to the shop

and buy a milkshake! There's just so many people's permission you've got to

get every time you want to do something."

With the recent success of the band's Starfish, it looks like a compromise of

sorts has been struck; the group will for now remain intact, sharing much of

the songwriting chores, while each individual member is free to release any

side project at his whim. This pleases Kilbey, who admits to being forceful

and opinionated in his quest for musical expression. "Basically, the band is

a democracy, but sometimes I have to veto that democracy and override things.

I know what I want to do, and sometimes apparently there isn't much room for

anyone else. Now we kind of write songs together. You know, we write the

music together, and then I write lyrics. Everyone assumed that I was forced

into that by the rest of the band, but it was actually my idea to share the

creative burden and also share the economic rewards," he reveals.

Earthed is Kilbey's first foray into poetry. While past solo works intersected

musically with the band, this has little in common, wedding a 76-page booklet

of his eccentric "automatic writing" to a 20-track, 47-minute collection of

ambient pop instrumentals. Though for the average reader the music runs out

before the text ends, it serves as a soothing soundtrack, with musical mood

swings that actually correspond to themes and passages in the book. "All the

things on Earthed (except for one piece) were written for that album

specifically. With the poetry already written, I'd just sit down and think,

'What's Neuman to me?' There's a fictional character called Neuman all through

the book. I'd think about it and the music would just come out."

In reading Earthed, it's quite difficult to mentally divide Kilbey's stanzas

into individual "poems." The text flows wildly, mixing colorfully surreal

images with purposefully vague historical references as time and reality are

spontaneously juxtaposed in a way only Kilbey could conjure up. "It's sort of

like I just sit there and make up a whole lot of stuff and write it down . . .

I like to call it automatic writing. Over here they call if stream of

consciousness," he says, seemingly in awe of his own gift. "I believe that

there's a vast untapped world below your conscious mind that knows a lot more

than you think it knows. If you can tap into this, whatever you want to do,

it's there. I think all the best writers do this. I was just reading this book

about August Strindberg the Swedish writer (of the late 19th century), and he

was saying the same thing. He doesn't know how he writes. He just knows that

for three hours a night, between 9 and 12, he used to just sit down and it

would flow and he didn't know where it was coming from. Then, after three

hours, it would stop. That's kind of how I wrote my book. I just had this

routine. I'd sit down at night after dinner and maybe smoke a joint or

something and just start writing. Eventually I ended up with this book. Then I

decided that it would be nice to have some music to go with the book."

As a musician, Kilbey has grown immeasurably. No longer just a bassist, he

plays virtually every instrument on his solo releases. "I'm that sort of

musician that, if you put me in the studio with an instrument, just by using

the technique of the studio, I'll create the illusion I can play," he

confesses modestly. "I've got a sequencer and a piano and, on my latest record

(The Slow Crack), people are saying, 'Fuck, you can really play blues piano!'"

When concentrating on his instrumental side (Earthed and selected tracks from

his previous LP, Unearthed), one influence pops up again and again. "Eno has

been an inspiration and example to me for a long time. I just think he's a

very intelligent man. He's kind of singlehandedly developed a certain style of

music . . . ambient music. I like everything he's done and everything he says.

When you get sick of the Motley Crues and the David Coverdales, you can think

'Well, this world has tossed up so me worthwhile people as well as all the

dross,'" Kilbey proclaims.

Kilbey the songwriter is another story altogether. Not satisfied with being a

garden variety pop lyricist, his lyrics are open-ended in a purposeful attempt

to generate some thought on the part of the listener. "I try to set up lyrical

situations where people start using their own imaginations as sort of a diving

board. I've just got this feeling that there is more going on than meets the

eye. I think that song lyrics or 'pop' songs should address these things more

than they do. There are combinations of certain types of music and certain

sets of lyrics that can spark off feelings in people . . . even provoke some

expansion of thought."

Yet Kilbey shies away from over-explaining his messages. "I feel that once

I've written a song, it becomes public domain in that my interpretation of

that song is no more valid than yours or someone who's just bought the

record. It can be anything. I purposely keep it open ended because I think

something that can be reinterpreted over and over again has more longevity.

If you buy a record and it says, 'Nixon's a cunt . . Reagan's a prick . . .

let's bomb fucking Russia,' I mean, that's great and it's a very positive,

direct statement, but after two weeks you don't wanna hear that all the time

because you've sucked all the meaning out of what you can get out of it.

Whereas I think the very best songs throughout the ages are more open-ended."

Pressed for a few examples, Kilbey's answers are surprisingly broad. "Some of

the songs that Frank Sinatra used to sing had very ambiguous kinds of lyrics.

'Witchcraft,' 'Misty,' you know, songs like that. Right through to the

Beatles when they were serving us 'Strawberry Fields,' the Simple Minds doing

'New Gold Dream.' It's just impressions and vague scenarios and suddenly your

mind takes over, you fill in the gaps yourself."

The Slow Crack, Kilbey's latest release, is clearly his most diverse

collection to date. Eschewing instrumentals entirely this time, the eight

songs vary widely, from a musical interpretation of Shakespeare's The Tempest

("Ariel Sings") to an obscure cover tune (Company Caine's "A Woman With

Reason," a Dylanish folk-rocker circa 1971). The album's title is an example

of the less obvious things on which Kilbey's mind tends to dwell. "I live in

a terrace house. For some reason, the back part is gradually separating away

from the front. Eventually my kitchen will end up in the back garden because

of this persistent crack that's growing larger every day! This builder came

out to have a look at it one day and told me, 'What you've got here is a

slow crack.' I just thought that was a great name for my next album," offers

Kilbey. The title took an ironic turn when Kilbey told fellow Church member

Willson-Piper about it. "I mentioned the album to Marty and he thought it was

pretty funny. He said, 'What you really mean is the slow crack between

yourself and the rest of the band.'"

At least for now, the crack has been patched. "We don't get involved with what

each other does solo," Kilbey says when asked about Willson-Piper's and fellow

Church bandmate Peter Koppes' recent releases. "I realize they have their trip

that they want to do, and I'm quite happy for them to do it. I'm just very

neutral towards it. I think it's really good for the Church that they go out

and do something on their own, though.

"I like ambitious things that fail," he says, referring to his solo work as

well as much of the band's. "I think some of my favorite things are failures.

That's why I like myself so much. I'm not talking in terms of sales, I'm just

talking in terms of feeling like I'm achieving something with it, you know? I

don't believe in the accepted idea of pop music. I just can't accept that pop

music can't deal with cosmic things," he states adamantly. Slow cracks aside,

it's obvious that Kilbey likes to grapple with the big questions as well

"I change my mind all the time," he sighs. "Sometimes I sit down and think

I've got the meaning of life sussed, and other times I realize I'm just an

idiot."

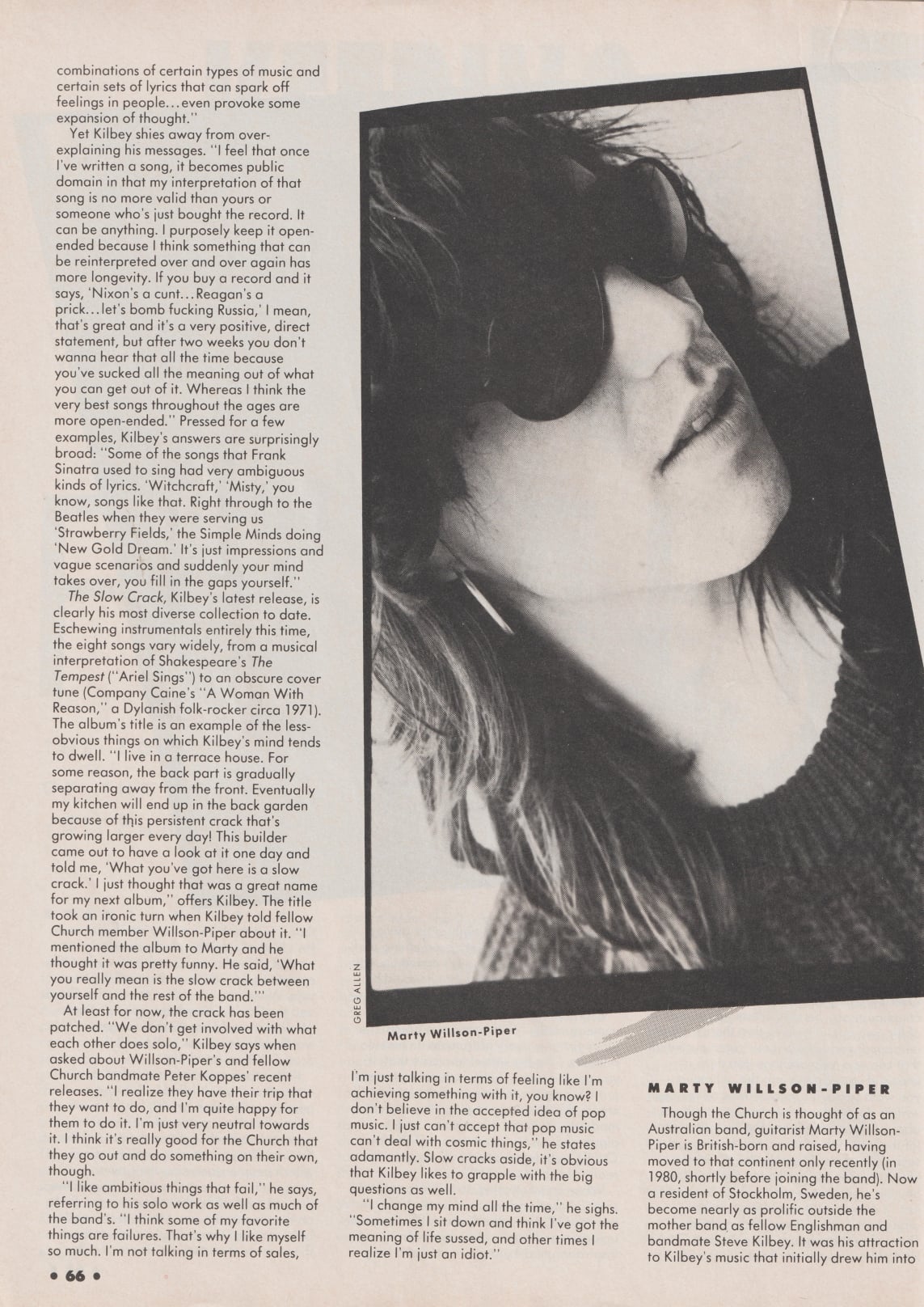

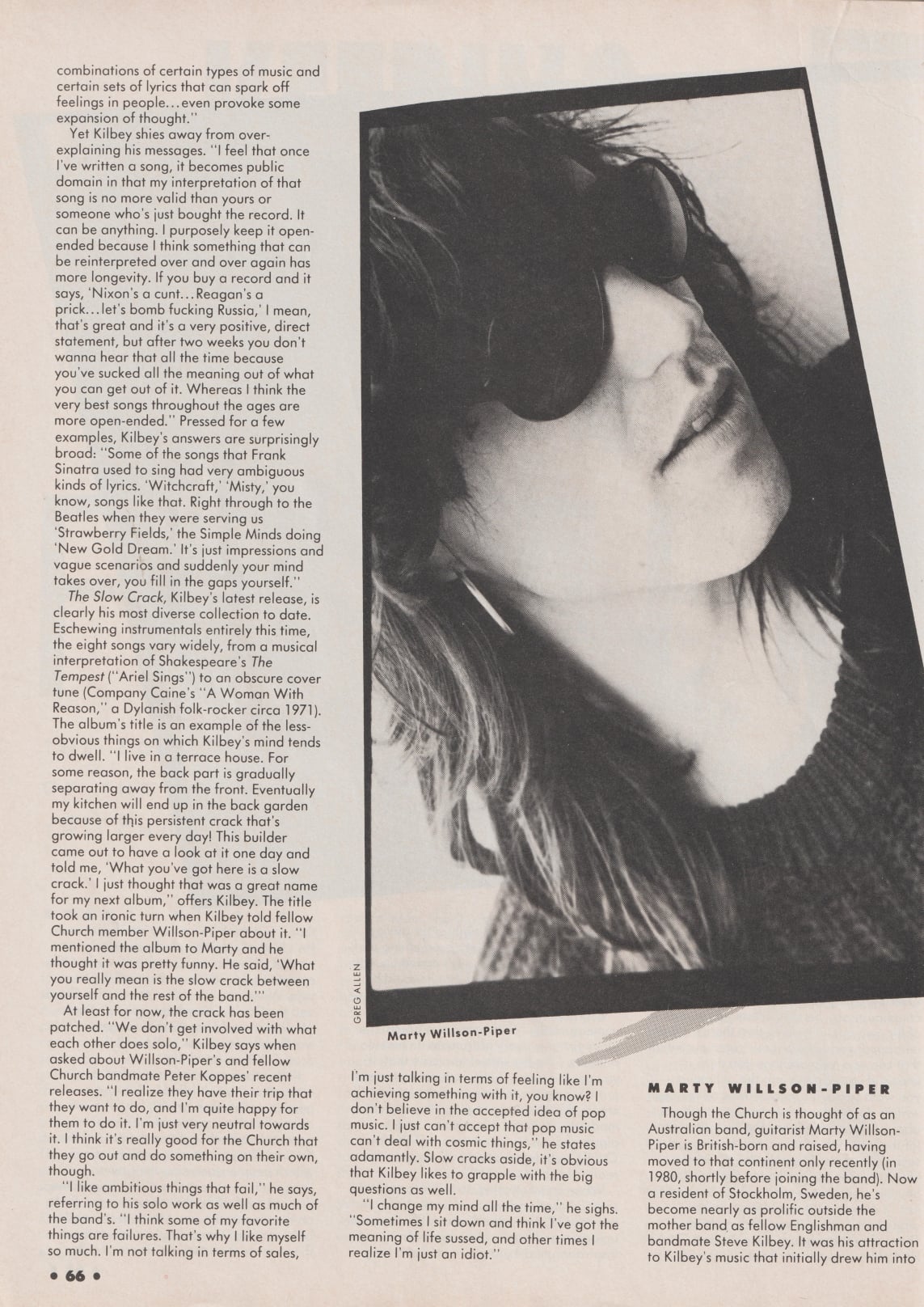

M A R T Y W I L L S O N - P I P E R

Though the Church is thought of as an Australian band, guitarist Marty

Willson-Piper is British-born and raised, having moved to that continent only

recently (in 1980, shortly before joining the band). Now a resident of

Stockholm, Sweden, he's become nearly as prolific outside the mother band as

fellow Englishman and bandmate Steve Kilbey. It was his attraction to Kilbey's

music that initially drew him into the group, convincing him to temporarily

abandon his songwriting and focus his energy on his guitar playing and band

arrangements of Kilbey's material. "I've always been quite a prolific

songwriter, but when I joined the Church I just really thought that the

atmosphere of the band was really great. I was prepared to go along and just

play guitar in this band for a while," reflects Willson-Piper

"I don't know really what I was thinking about my own songwriting or where

that was going to fit in," he continues. "The band writes most of the songs

together these days anyway."

Though both Willson-Piper and fellow guitarist Peter Koppes contributed

heavily to the music on Heyday, their solo tracks were cut from the album

proper (though they appear on the cassette and CD, and as B-sides to singles).

Perhaps not coincidentally, during the long Heyday tour, Willson-Piper briefly

walked out on the band. "I quit out of frustration for the whole affair. I

had just been on the road a long time," he reveals. "I look after a lot of the

business stuff for the band as well, and I wasn't getting much out of touring

around playing songs; not singing, not writing, not getting songs on records.

Steve and I just reached some kind of philosophical rift and it results in me

saying goodbye. So I quit, but then quickly realized that it was a stupid

thing to do. I came back to the band and decided I wasn't gonna cause any

problems . . . just work on my own stuff to relieve the problem of the

frustration I had rather than making everybody else's life a misery too."

Which brings us to In Reflection, Willson-Piper's solo debut of last year.

Recorded on four-track between 1983 and 1985 while on breaks from the band,

it's a 13-song collection of Church-influenced, psychedelic pop, instrumental

excursions, and even one band song in rough demo form ("Volumes"). An amazing

booklet of song-by-song home recording techniques and insightful anecdotes,

along with lyrics and pictures, accompanies the album. Willson-Piper is an

outgoing fellow, anxious to reveal and share, an obvious contrast to the

highly enigmatic Kilbey. "I have a different approach and Steve has his way

and Pete his," he notes. "I mean that whole booklet idea is something that

Steve or Peter would never do with the Church."

Of the three songwriting Church members, Willson-Piper is clearly the most

political, though his references are usually veiled to some degree. Regarding

the anti-war sentiments on "Volumes" he explains, "Well, actually, I'm a big

reader. I read a lot. The point behind that song was that nobody does read.

Everybody's more concerned with the violent aspects of the world. I was trying

to encourage people to bury their heads in books and be bookworms." Asked

whether this meant filling one's self up with philosophy and doctrine, he

offers, "Yes. I think filling yourself up with doctrine is one thing. When

filling yourself up with words which are philosophies you don't have to a)

agree with, b) be affected by it, or c) take it seriously.

"By philosophy I mean stuff like Bertrand Russell and Erich Fromm, who was a

German writer [and psychologist]. I've been reading a lot of French things

recently. Things like Albert Camus. He's fantastic . . . he justifies jumping

out of windows, that sort of thing. You don't take it that seriously, you

just get from it what you will and take the positive side of his ideas.

That's what I do myself. He just comes up with things that blow my mind."

Willson-Piper eagerly continues, "I'm just reading this book by Camus at the

moment which is about the absurdity of life. It's called The Myth of

Sisyphus. Well, he upset the gods and was punished by having to roll a rock

up to the top of a mountain for eternity. When he got to the top, the rock

would roll down again! It's just an incredible book."

Art Attack is Willson-Piper's latest. Recorded on eight tracks, it's generally

less layered and textural than his debut, with some tracks utilizing stark,

stripped-down arrangements. A former "street musician," Willson-Piper's

dominant instrument this time out is his acoustic 12-string guitar, accounting

for the folky feel of many of the songs. The range on this new album is vast.

Interspersed between the folky pop gems are tracks like "Evil Queen of

England" (a direct, venomous attack on Thatcherism with just bass and vocal)

and "Word" (eight-plus minutes of beatific, echo-laden word clusters, starting

out a cappella and building with guitars). Some of these arrangements come

off as more spontaneous than anything the band or any of its mem

bers have ever recorded.

"I just went to New York and made the whole album in two weeks. I didn't use

any of my own instruments," says Willson-Piper. "I just walked into this cold

studio and just suddenly . . . and I like doing that. I like putting myself

into those positions. Putting myself in a situation where anything can happen.

I mean, I actually wrote two songs in New York while I was there." As with his

LP In Reflection, the majority of the instruments, vocals and songwriting

chores (one track is co-written with girlfriend Ann Carlberger, who also

sings) fall to Willson-Piper. Lifelong friend Andy Mason helped with

production as well as contributing backing vocals, occasional guitars,

harmonica, and half the keyboards. "He's a big influence on me. Although I

write the songs and come up with the musical direction to a certain degree,

he's great . . . whatever he says, I listen to. I've known this guy all my

life, since I was three. We've been friends all through that and have been

through a lot of things together. If we don't see each other for a year and

then we walk into a room together, it's like we saw each other yesterday,"

confides Willson-Piper. "It will always be like that. Consequently, I always

want him to work on albums that I do."

As with the Church, many fans and critics have pointed to various influences

in Willson-Piper's music, real or imagined. "Some people ask me about Syd

Barrett and what influence he had on me. I like that kind of music. I don't

really make a conscious effort to rediscover the '60s or Pink Floyd, but I do

have a tendency to have a soft texture in my voice on some of the songs,

which is very similar to that kind of music. But I also like Robyn Hitchcock.

I've got all the Soft Boys albums even, you know. I know that Robyn Hitchcock

likes the Church. Somebody told me that once," he says with pride.

While the Church is somewhat of a pop act, it's clear that Willson-Piper is

pursuing his own muse through his solo releases. But where does he draw the

line between creativity and commercialism in pop music? "'Who Will You Run

To?' by Heart means as much to anybody as anything the Church ever wrote, you

know," he says offhand, wanting perhaps to appear either modest or open-

minded. "I think it does. I don't know if I'm right to write just for myself.

I think all I'm saying is that it's probably just as relevant to purposely go

out and write songs for 16-year-old girls.

"Heart and the Velvet Underground . . . what's the difference? I think the

Velvet Underground are special. Somebody else thinks they're a pile of rubbish

and that Heart says a lot more than they ever did. And they're probably right

for themselves. It's really hard to compare and judge music in any way,

whatsoever.

"It's funny," says Willson-Piper. "Just to go back to old Camus for a moment,

he wrote a book called The Fall. It's about this lawyer. The point was that he

was a successful lawyer who came to the great conclusion that a man can never

judge another man from the point of righteousness."

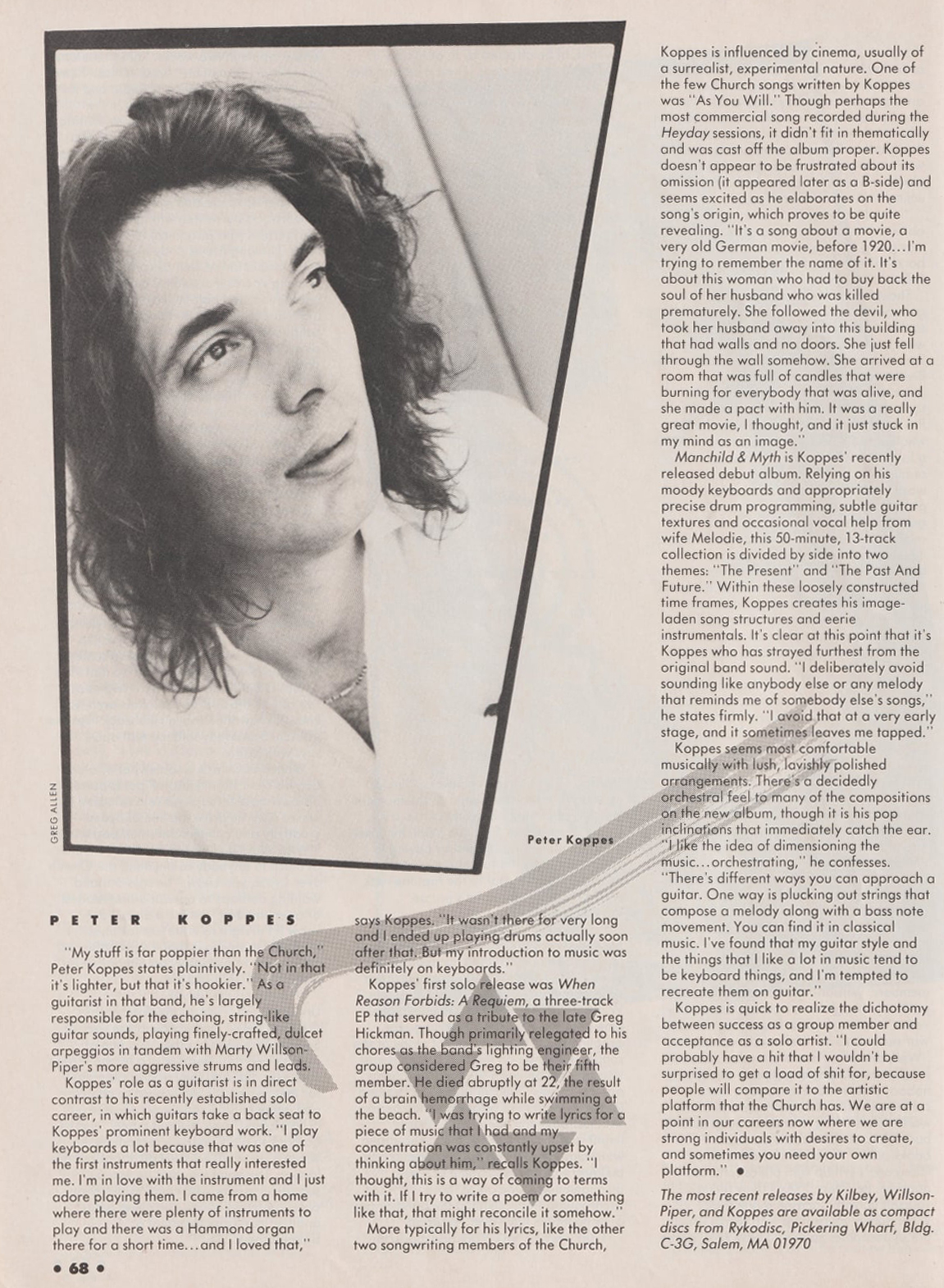

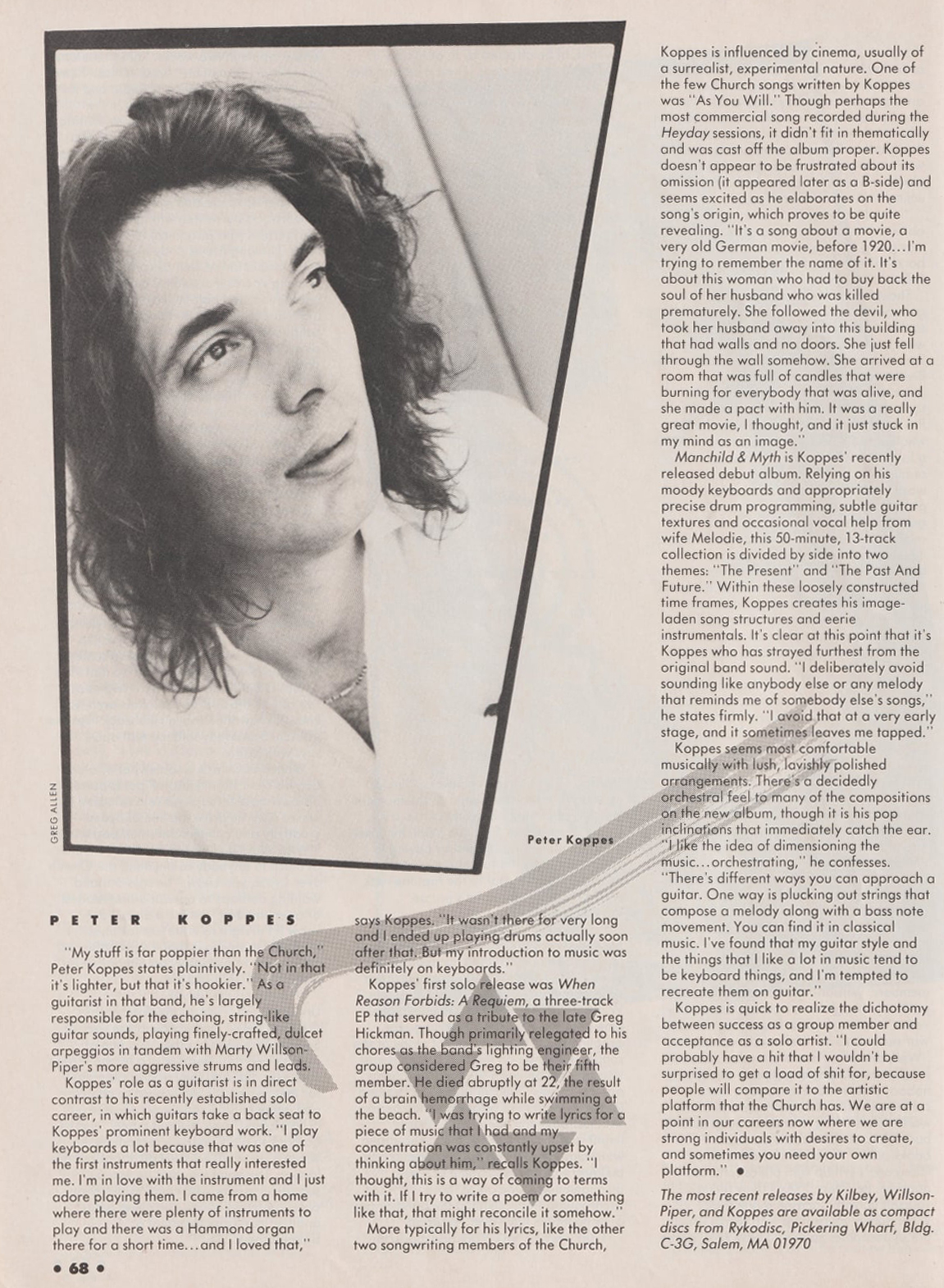

P E T E R K O P P E S

"My stuff is far poppier than the Church," Peter Koppes states plaintively.

"Not in that it's lighter, but that it's hookier." As a guitarist in the band,

he's largely responsible for the echoing, string-like guitar sounds, playing

finely-crafted dulcet arpeggios in tandem with Marty Willson-Piper's more

aggressive strums and leads.

Koppes' role as a guitarist is in direct contrast to his recently established

solo career, in which guitars take a back seat to Koppes' prominent keyboard

work. "I play keyboards a lot because that was one of the first instruments

that really interested me. I'm in love with the instrument and I just adore

playing them. I came from a home where there were plenty of instruments to

play and there was a Hammond organ there for a short time . . . and I loved

that," says Koppes. "It wasn't there for very long and I ended up playing

drums actually soon after that. But my introduction to music was definitely on

keyboards."

Koppes' first solo release was When Reason Forbids: A Requiem, a three-track

EP that served as a tribute to the late Greg Hickman. Though primarily

relegated to his chores as the band's lighting engineer, the group considered

Greg to be their fifth member. He died abruptly at 22, the result of a brain

hemorrhage while swimming at the beach. "I was trying to write lyrics for a

piece of music that I had and my concentration was constantly upset by

thinking about him," recalls Koppes. "I thought, this is a way of coming to

terms with it. If I try to write a poem or something like that, that might

reconcile it somehow."

More typically for his lyrics, like the other two songwriting members of the

Church, Koppes is influenced by cinema, usually of a surrealist, experimental

nature. One of the few Church songs written by Koppes was "As You Will."

Though perhaps the most commercial song recorded during the Heyday sessions,

it didn't fit in thematically and was cast off the album proper. Koppes

doesn't appear to be frustrated about its omission (it appeared later as a B-

side) and seems excited as he elaborates on the song's origin, which proves to

be quite revealing. "It's a song about a movie, a very old German movie,

before 1920 . . . I'm trying to remember the name of it. It's about this woman

who had to buy back the soul of her husband who was killed prematurely. She

followed the devil, who took her husband away into this building that had

walls and no doors. She just fell through the wall somehow. She arrived at a

room that was full of candles that were burning for everybody that was alive,

and she made a pact with him. It was a really great movie, I thought, and it

just stuck in my mind as an image."

Manchild & Myth is Koppes' recently released debut album. Relying on his moody

keyboards and appropriately precise drum programming, subtle guitar textures

and occasional vocal help from wife Melodie, this 50-minute, 13-track

collection is divided by side into two themes: "The Present" and "The Past

And Future." Within these loosely constructed time frames, Koppes creates his

image-laden song structures and eerie instrumentals. It's clear at this point

that it's Koppes who has strayed furthest from the original band sound. "I

deliberately avoid sounding like anybody else or any melody that reminds me

of somebody else's songs," he states firmly. "I avoid that at a very early

stage, and it sometimes leaves me tapped."

Koppes seems most comfortable musically with lush, lavishly polished

arrangements. There's a decidedly orchestral feel to many of the compositions

on the new album, though it is his pop inclinations that immediately catch

the ear. "I like the idea of dimensioning the music . . . orchestrating," he

confesses. "There's different ways you can approach a guitar. One way is

plucking out strings that compose a melody along with a bass note movement.

You can find it in classical music. I've found that my guitar style and the

things that I like a lot in music tend to be keyboard things, and I'm tempted

to recreate them on guitar."

Koppes is quick to realize the dichotomy between success as a group member and

acceptance as a solo artist. "I could probably have a hit that I wouldn't be

surprised to get a load of shit for, because people will compare it to the

artistic platform that the Church has. We are at a point in our careers now

where we are strong individuals with desires to create, and sometimes you need

your own platform."

Return to 1988 index